An excerpt from my next book* : my take on peer reviews and value engineering.

* Book is currently under construction, due early 2019 with the working title ‘From Failure to Finish Line’.

——————————-

PEER REVIEWS

To assist with creating coordinated and quality documentation consider peer reviews. Peer reviews are undertaken by independent consultants who are not influenced by the history of the project, or the people involved, to provide an objective review. The best peer reviewers (as far as objectivity goes) are those who don’t succumb to using the peer review process as an opportunity to tout their own services. You know, to try and become your replacement consultant on the project! That’s a touch cynical but I have seen it happen.

Peer reviews may have been included in your audit during due-diligence. Albeit if you had time constraints they would have been limited to high risk issues. This time you are focussing on moving the project forward. Of course, you can peer review anything. But the objective is typically to confirm that the plans and specifications are sound and fit for purpose. Where they aren’t you should expect to be provided with alternative viable options to consider. However, look at taking it one step further and instruct peer reviewers to be on the lookout for high value opportunities as part of their advice.[1]

The type of project and where potential risk currently lies will influence what you conduct peer reviews on.

- Consider a house and land development where civil infrastructure works or house building has yet to start. A peer review of the civil engineering and geotechnical documentation, in conjunction with the home architectural site layouts is important. Considerable construction cost escalation risk exists in ground for many sites. The review could also include examining structural foundations, retaining walls and finished floor levels to make sure it all lines up and the most cost-effective method is being utilised. The cross-over between civil engineer, structural engineer and architect can be complicated. From my experience that is a rich source of improvement – to uncover conflicts that become very expensive to fix during construction. Whether you decide to peer review the above foundation house documentation might depend on its complexity and your familiarity with the product type – i.e. a low risk might not justify a peer review.

- For a multi-level apartment or office building, consider peer reviewing the structure (including frame/floor assemblies, piling and foundations), façade weather-tightness, fire and acoustics and potential service clashes (or opportunities to streamline services vertically).

- On a large industrial building a peer review might be limited to the roof structure and wall assembly that is enabling wide spans and a high stud. This is something that can easily be overengineered.

Don’t just leave it to formal construction and engineering reviews though. Tackling a thorough design and market assessment peer review might be worthwhile – if sales or leases are still required. Typically to do this you will engage with real estate sales or leasing agents[2] and specialist designers. You might also include the advice from a market research expert, appraiser or valuer. For example:

- For a retail centre a design peer review may question circulation, service area and wasted space in relation to lettable area.

- The design review on an affordable apartment project may concentrate on kitchen and bathroom layout efficiency.

- A high-rise office design and market assessment review might take an alternative approach to analysing the spatial requirements for your markets key anchor tenants (like space per occupant for law firms and banks).

VALUE ENGINEERING

‘Peer reviewers’ are better at reviewing what exists than finding new opportunities. Value engineering is that next step. This is where you adjust your plans and specifications to increase profit. It may well be that the opportunity for you to take over this failed project only exists because of your expertise at value engineering.

It should really be called profit engineering.

This is an important point. All too often value engineering becomes a purely cost cutting exercise, whereby deletion becomes the default answer. Even worse, I have also seen so called value engineering, especially in the substitution of design or materials where the change has a negligible effect or increases the cost, because of some unforeseen implication. You might save on the raw material cost, but the new installation cost exceeds the benefit. Or by the time you factor in the fees for architects and engineers to change drawings and achieving a new building consent, it turns out to be never worth the effort. Also, often over looked is the negative impact a cost reduction can have on a sales or rental price. The sales price might drop more than the savings you have made.

Done well, value engineering should focus on the relative beneficial impact of a cost cutting decision on revenue (i.e. does it create more profit margin). Rarely done, is when you value engineer by adding cost to increase revenue. Positive value is achieved when the increase in revenue is higher than all the costs to get there. At some point though, if you do enough value engineering, you are effectively repositioning the project, which we discussed in the restart chapter.

There are three ways you can undertake a value engineering exercise:

- Ad-hoc via contractor

- Project team approach, or

- Elemental and functional investigation.[3]

Building upon what you may have already uncovered in your due-diligence audits and peer reviews each approach progressively becomes more involved. Number 3 requiring more preparation and management dedication and will take longer and can cost more.

Ad-hoc via Contractor

The ad-hoc via contractor led approach is where you, your builder or a construction expert review the plans and specifications and mainly through experience find an element or three that can be substituted or deleted. That’s commonly about as much as you expect when you hand a contractor some plans and say we are open to all value saving opportunities. That’s because few contractors have an appreciation of the effect of any VE change on value, town planning regulation, design aesthetics and other subtleties. So, either they offer up savings with changes that are simply not possible or desirable, or become too conservative and make an assumption that because something is shown on the plans it is required. A contractor well experienced in your product type in your product market should be much better at value engineering.[4] That is because they have already been through the value engineering hoops with other developers and their teams.

Project Team Approach

The project team approach is where you ask each project team member to review their own work and offer up a list of value engineering options. In consultation with your sales or leasing agent review each option for impact on sales or rental value. Immediately exclude any that make so sense from a sales or leasing point of view. For example, there may be some you can’t get away with because of pre-committed purchaser or tenant contracts. For the options that retain merit, hold a value engineering workshop (or two) with the entire project team to work through the implications of making the change. Using a quantity surveyor or professional cost estimator calculate each options’ potential savings (or costs if there is a net gain to be made by adding cost to increase revenue). This professional cost advice now puts you on a firmer footing to run the idea past the contractor for buildability and actual savings. This helps prevent the contractor brushing off perfectly sound suggestions due to ignorance or a lack of incentive to investigate the item further. The project team approach leverages the collective experience of all team members so also works better if they, each individually, have experience on similar type projects in similar markets. The downside is some will simply not be able to review their own work and come up with any bright value engineering ideas. Whether an inner reluctance through arrogance ‘all their thinking has already been done’. Or simply they have been tuned into such a precise frequency that they can’t imagine a different harmony. So, this approach ordinarily works better when you have replaced consultants and contractors, rather than kept existing ones.

Elemental and Functional Investigation

The third approach is just a more meticulous and methodical combination of the above. This is the elemental and functional investigation (apologies I can’t think of a catchier name). This takes more preparation and management but can yield much better profit improving results. It can also show up project team members who are not delivering their A-game as well as deficiencies in documentation.

An element is a specified item such as tile flooring, steel columns or timber decking. Whereas a function represents the required output for the built form, such as flooring, structure to hold up each floor, or even as ethereal as ‘desired private outdoor space’. Considering the function helps creatively expand the thinking of what could be changed or how to achieve the same output differently to increase profits.

Here’s my eight-point process – undertaken prior to formally tendering or lodging consent but including early contractor involvement – using a spreadsheet.[5]

1.Create a spreadsheet where each tab is associated with a different element or functional requirement that you intend to value engineer. What items you consider will depend on how far through the project you are and what can realistically be changed now. For example, you can’t change the foundations if the project is already into the wall framing stage. Similarly, you may not be able to change cedar cladding if that was a hotly debated specified item forced upon the project at town planning consent stage. You can approach each project team member to provide a list of their ‘items for consideration’. Note though that some will be bias or reluctant on what they provide. I have found nothing is better than going through the plans, specifications, the quantity surveyors elemental cost analysis and the contractors sub-trade list to extract these items yourself. For each item include the relevant plans and specifications, indicative pictures (or actuals if you are looking at a renovation) and anything else that can add to a critical analysis discussion. Include the current cost and if you already have an idea of where your budget needs to be, your target cost. Cost is easier to identify for a single element than for a function – but you should still try to identify the relevant cost parameters that make up a function. If there is a lot of documentation for an element or functional output, then just include a summary on the spreadsheet tab and a reference link to full documentation.

2. To focus the analysis, arrange the items (tabs on your spreadsheet) in a logical order. The best (time versus impact) approach is to order what are likely to be the big-ticket cost versus revenue items as top priority and then work your way down the value chain. Spend more time on the big savings for little revenue impact, and less time where savings are likely to be smaller. For example, on an office building you might start with foundations, car parking, super structure and curtain wall glazing and then move onto vertical circulation, heating and air-conditioning before looking at internal partitions, suspended ceilings, bathrooms and common area finishes. An alternative ordering (eliminating assumptions on what could be the most profitable VE before you do the analysis) would be to simply start at the physical bottom and work your way up and out generally in accordance with a construction programme. For example, on a house development start with site preparation, demolition, earthworks, services and then foundations, structure, roofing, cladding, windows to flooring, kitchens, bathrooms, finishes and fittings.For an old apartment building with historic protection that we were about to comprehensively renovate our priority order was based twofold. One, what items had no effect on the historical preservation, and therefore we could VE to our hearts content. That list was then prioritised by the quantum of renovation cost, looking at big ticket items first. An example was ‘weatherproofing the external walkways’. And two, what items could trigger a ‘no’ from the historic preservation trust if they were changed. That list was prioritised by the limitations of possible value engineering changes. If few possible changes then little point discussing it and it fell to the bottom of the priority list. Keeping the façade on one street frontage exactly as it was built was an example here where there was no point trying to value engineer.

3. Distribute the spreadsheet to the team members you wish to involve in the VE exercise. You might need to a kick off meeting at this point to get buy-in from whom you want involved. Expectations around how much time to be spent, costs incurred and deadlines for feedback should be set at the outset. On the spreadsheet include a summary tab that lists each item as well a distribution list for that item. Not all team members will be able to contribute to every item, nor should you waste time doing so. There is no point for example involving the interior designer on foundations or a steel fabricator on floor finishes. The architect, cost estimator and/or contractor do need to be involved in each item. For some items involving key subcontractors and potential suppliers may be beneficial. Within each item tab, add the distribution list with a space for their review comments.

4. Have each team member analyse their relevant items. This next step is probably the most powerful part of the VE process. To promote creative and critical review, include these question prompts:

- Reprice: Is this a competitive market accurate cost estimate?[6]

- Deletion: Do we need this item?

- Addition: What can we add to make it better?

- Substitution: What else could do the same job?

- Simplification: Is this (system/installation) overly complex to achieve the intended result?

- Systemisation: Is there a proprietary system available?

- Specification: Is this a higher quality than is required? What if we decrease / increase the quality? Can we provide more / less functionality? What if take a longer/shorter lifecycle view?

- Resource: Can we share, group or combine this function?

Let’s use the function “kitchen” in a multi-unit retirement development to illustrate.

- Reprice: Is our subcontractor used to pricing this volume?

- Deletion: Remove cabinetry and turn a U shape into a L.

- Addition: Add an island

- Substitution: Swap benchtop granite with engineered stone.

- Simplification: Why not a single unit mini kitchen.

- Systemisation: Build the walls to fit a flat-pack kitchen.

- Specification: Upgrade appliances. Downgrade door handles.

- Resource: Kitchen to be shared between two units.

If we then focus on the element ‘kitchen bench’.

- Reprice: Order very early at discount.

- Deletion: Decrease the depth of kitchen bench.

- Addition: Add kitchen bench material to back-splash.

- Substitution: Replace marble with porcelain.

- Simplification: Create a one piece top with sink out of same material.

- Systemisation: Make each benchtop exactly the same size in accordance with least wastage from sheet sizes.

- Specification: Downgrade from Italian marble to Indian marble.

- Resource: Use the same supplier and material for kitchen benchtops and bathroom vanity tops.

The analysis and individual ideas should be summarised in the spreadsheet tab and all supporting documentation sent through (and referenced on the spreadsheet tab).

5. Consolidate all the replies into a single master spreadsheet, with consistent formatting. Some items will have few comments or none (i.e.no one could figure out any VE to improve upon), whilst others will attract many. This is the time you follow up and be somewhat persistent to extract VE ideas. You want to make sure everyone has given it their best attention.

6. Convene a value engineering workshop. Ask all team members to bring any further supporting evidence to their alternatives and ideas. At this workshop systematically go through each potential alternative/idea addressing the implications on.

- Revenue

- Marketing and buyer/tenant appeal

- Construction cost

- Redesign cost, time and coordination

- Linkages to other items

- Contracts

- Timetable and lead times

- Consenting risk

Like most brainstorming sessions it is important not to dismiss ideas too quickly, especially if project team members are not aware of the full picture. Firstly, you want to encourage ideas and not have people hold back out of worry of how it will be received. Secondly, what is a stupid idea to one person might be a fantastic idea to another and vice versa. For example, the structural engineer might propose to add columns to support a protruding cantilevered wing for a coastal hotel project – she is so confident this VE will save hundreds of thousands of dollars and has no idea why no one else thought about it. But the architect and developer, given years of painful planning consent hearings know all too well that the only reason this project exists with so many rooms and a half chance of being profitable is because of the cantilever. They have sold the community on the cantilever being an architectural ecological metaphor to a local and almost extinct seabird soaring into the air…(believe me it can get worse than that!). Thirdly, if you do dismiss an idea whether by group consensus, a vote (or because it really is stupid) at least provide a well-reasoned argument to support your position, so the promoter of that idea at least understands why and won’t get despondent.

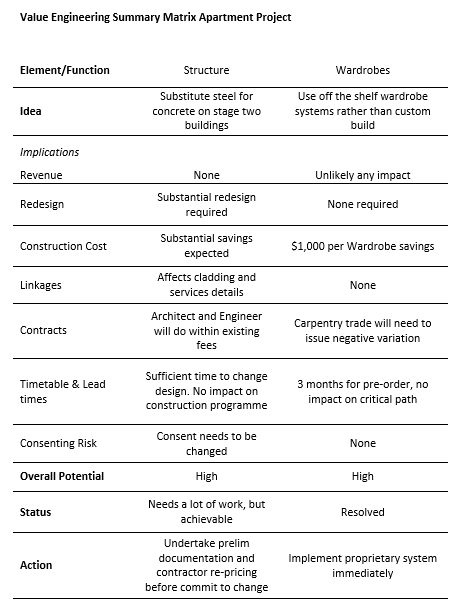

7. Many ideas will prompt questions, bring issues to light and require further research and investigation that cannot be resolved at the workshop. Unless your team are going to delve deeper without charging you (and in quick time), you may want to limit further analysis to those alternatives and ideas that look the most promising (profitable). Once again focus on the big savings first. However, enough small savings can start to add up. You will need make a judgement call on how far to let the team have another go before further investigation becomes counterproductive.Arrange the results of your workshop into a summary matrix. On this assign a status in relation to how knowledgeable you are with the potential cost versus its benefit and what action to take next. Here’s an example summary matrix for two ideas gleaned from a VE workshop for an apartment complex project:

8. Finally, direct the team to further investigation or work towards implementing the more profitable idea.

With a balance between being methodical, realistic and creative that’s how we value engineer!

————

Cheers

Andrew Crosby

Real estate development books now available via Amazon or direct from publisher in New Zealand. Contact publishing@aenspire.com for special rates. Go to www.developmentprofit.com to view publications available.

Notes:

[1] Formal peer reviews by engineers are often regulated by their industry associations, so there may be limitations on how far a peer review is able (or willing) to critique the work of another.

[2] By their nature, every real estate sales and leasing agent is bias, and would only bother looking at your project in they thought they have a chance of getting the listing. So the term peer review is used loosely in this context.

[3] Value engineering described by others, worth the read if you want to focus on this:

https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Value_engineering_in_building_design_and_construction

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ve/veproc.cfm

https://www.wbdg.org/resources/value-engineering

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/property-development-series-5-detailed-design-value-simon-lee

[4] As well as a much less risky prospect to build your project.

[5] This could be a shared spreadsheet, a word processing document, a physical scrapbook or a fancy purpose built online real-time collaborative forum and mark-up tool. In my case a spreadsheet works well enough – although I am tempted to build the latter. I believe the extra admin compiling responses actually forces you to consider them more in depth. Realtime review can also invite off the cuff comments rather than well-reasoned advice with evidential workings.

[6] Value engineering is not supposed to be about renegotiating supplier contracts to extract a better price for the same product. Of course, the very exercise of looking at alternatives that results finding a cheaper substitute, may increase your negotiating argument with an existing supplier.