The Developer Chronicles: Master-planned Projects

In this series, I describe master-planned projects. The discussion focuses on the difference between a one-off project and a multi-stage, multi-year planned development. I explore the factors that great development teams grapple with every day. I hope you find it of value.

AND you can also contribute to this opensource education by commenting with your own experiences, strategies, tactics and ideas here on LinkedIn. That’s where we can really embrace group network effects for continuous improvement in development management.

The DC: Master-planned Projects #3 Feasibilities

The financial feasibility is the guiding light for any real estate development. And the very bottom line represents everything about the project: the profit. I have written here about the profit before describing how it represents more than most people think. But at the end of the day profit drives projects. And at financial feasibility stage no profit = no project.

Profit and the Return on Cost

Everything you need to know about a project’s financial status is wrapped up in a single measure of profitability: the return on cost. The Return on Cost calculation is basic. The Return on Cost (RoC) is the Net Income (Total Sales less Total Costs) divided by Total Costs. Net Income is another way of saying Profit.

RoC = Profit / Total Costs

For example, if you proforma $10,000,000 of sales, and incur $8,000,000 of costs you have $2,000,000 of Net Income. That’s $2,000,000 of Profit. The Return on Cost is $2,000,000/$8,000,000 = 25%.

Some developers will calculate the Net Income slightly differently. They might use Gross Margin (margin is really just another word for profit) before sales commission, include commission in the costs, or take it from gross sales, either look at pre or post finance, include or exclude various taxes and place contingency outside of the equation. Similarly, the Return on Cost might have variations to it. It doesn’t really matter. I like to include every cost, including an allowance for finance and contingency and internal overheads and development management in the total cost denominator. Everything except income tax on net profit. That best represents the cash residual at the end of the today you can put in your pocket before having to pay the taxman.

Financial Feasibility

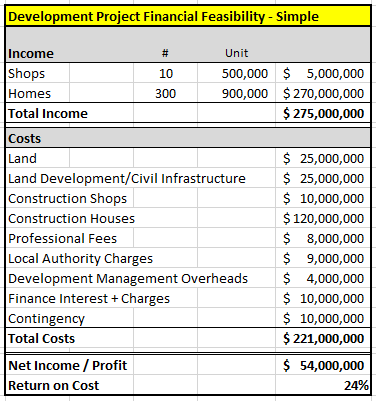

From hereafter I will simply refer to feasibility. What I specifically mean is the financial feasibility*. Not to be confused by an architect’s feasibility, which is just a bunch of drawings to demonstrate what and how many buildings could fit on the site. The feasibility can come in all shapes and sizes** but at the end of the day will include a summary something like this:

This simple feasibility is calculated in today’s dollars. It ignores the time value of money effect, except that the longer the project takes, the higher the finance interest cost will be. In today’s low-interest-rate environment, the time value is less meaningful anyway.

*For most of you reading this, I have not described anything new. If you are a novice and want to understand everything that needs to be included in a development project financial feasibility and how to build one then I have two suggestions: House, Land, Love & Money and Turnaround Success. In both books, I dive deep, fully deconstructing development project financial feasibilities.

**I also don’t buy into the need to have specialist proprietary software to create a financial feasibility. The software vendors will argue, that a spreadsheet can introduce too many errors. And they are right if you don’t either make the spreadsheet real simple, or integrate checks and balances. But my two main peeves with proprietary software are, one, it can be difficult to understand the assumptions under the hood. And two, no development project is the same and often the proprietary software doesn’t give you the flexibility as you require it. I prefer Microsoft Excel. Each to their own. The other thing I will add is that the size or complexity of your spreadsheet does not mean you are any better at predicting the future. Often a ten year feasibility broken down into monthly cashflows is no better predictor of the actual outcome than a few notes on the back of an envelope – keep this comment in mind later on. However, a more detailed feasibility does help you identify and quantify risk. This is another area where forcing yourself to to create your own feasibility is preferable to relying on input boxes where you don’t quite know how the outputs are calculated.

This type of feasibility is all you need for a one-off project. Assume the above represents an apartment tower (homes=apartments) built, in say three years, with presales before construction starts and a fixed price contract. The effect of time is all captured in the finance cost and presales and the fixed price construction price, prevent inflation or deflation having an effect. (This, of course, is rarely the case, even for a project that takes six or 12 months, but for feasibility purposes, it is a valid assumption).

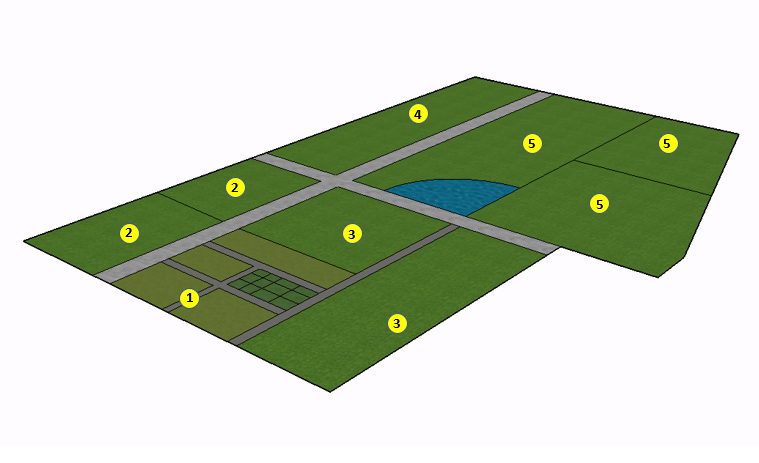

Now let’s consider a master-planned development feasibility. The summary might be no different. However, in my definition, a master-planned development takes place over several years, even decades and in various stages. Imagine something like this diagram.

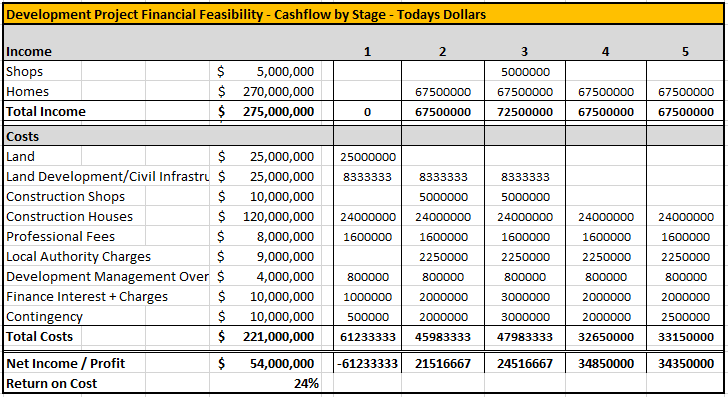

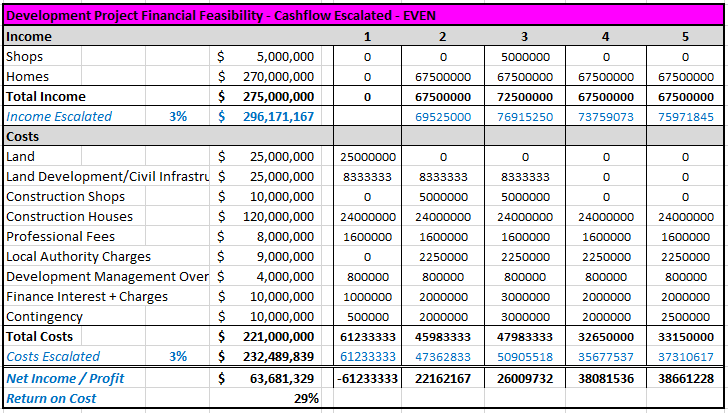

If we cashflow our summary out according to each stage (probably easier to think about stage and year as one and the same ) then the feasibility expands to look something like this:

It’s the same Profit $ and the same Return on Cost %. Nothing different to see there. But we have expanded the detail to show what revenue we expect to receive and expenses to be paid in each stage. If you want you could discount future stages and calculate the Present Value and the Internal Rate of Return, but I am not going there in this article. The main difference is the master-planned project typically takes a lot longer than the one-off project, all things else equal. (Plenty of standalone projects can be delayed years and decades because of market conditions or issues. I have plenty of examples here. But that doesn’t mean they become a master-planned development, it’s just they are a one-off with delays!).

Escalation

So let’s assume you have done all your due diligence, created a master-site-plan and are happy with all your sales projections and costings – in today’s dollars. And let’s assume each of the five stages shown above takes two years. That means this is a ten-year project. Do we really think we know where the real estate market will be in ten years time? No one has that power of prediction – despite what one might try and convince you. But, we are in the development business and we must make some financial projections to satisfy investors and funders. The tendency is to allow for inflation by escalating cashflows. I.e. we forecast (guess) that sales prices will rise and costs will also. That is an attempt to give us a more realistic view of the actual cash coming in and out in later stages. When we do that the feasibility will look like this.

Did you notice something? And every developer would have instantly. Even though we have escalated both income and expenses at the same 3% rate, we have magically created additional Profit and a higher RoC That is a function of two things: one, simple maths – revenue is higher than costs therefore if you escalate both at the same rate the profit gap will increase. Two, you typically incur costs in advance of sales, so there is less time to escalate costs and more time to escalate sales revenue. For one big-ticket item – the land purchase -it’s price does not increase. Infrastructure construction costs – bulldozing dirt and building roads – is also incurred in advance of above-ground building.

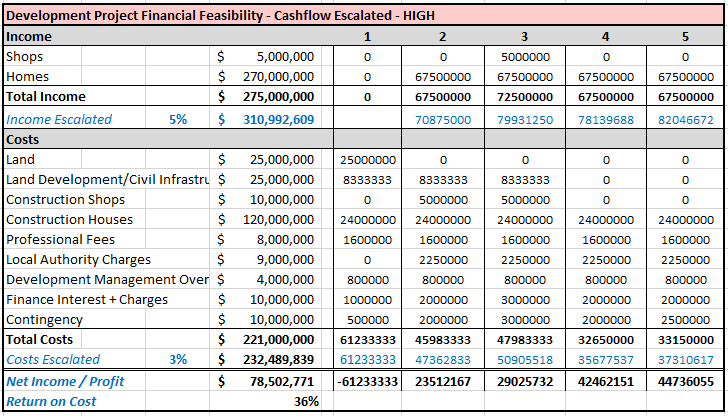

Few forecasters limit their optimism though. Especially if you have had previous years of sale price growth in the market place at five or more percent. It will be difficult to do anything but continue to forecast that trend into the future. Ironically few forecasts temper their pessimism regarding construction costs, even with five percent or more increases in previous years. The tendency is to limit future increases to inflation plus. Put those two optimism-bias based factors together and your feasibility might end up like this.

Look at all that profit! Note that we haven’t increased density and sold more properties. We haven’t value-engineered the design. We haven’t found a cheaper method of construction. We haven’t added marble tiles to the bathrooms to increase the sale price. No, we created 24.5 million dollars simply through the power of innocent escalation.

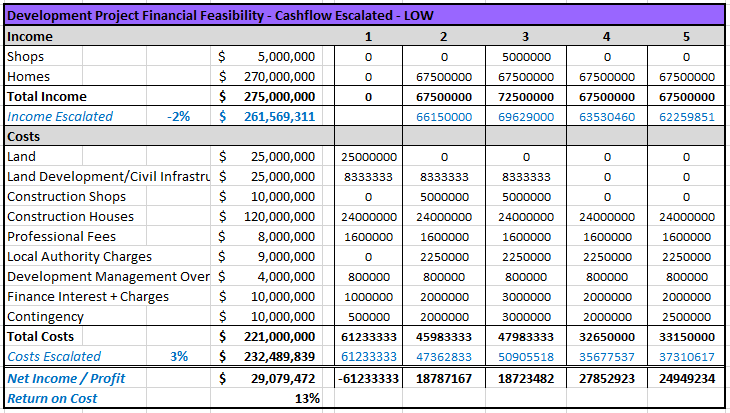

Now our escalation guesstimate might prove correct, you will never know until stage five is complete – in this case a decade later. But equally so the market might deteriorate. Why not put this feasibility forward?

I have never seen a feasibility presented to anyone who is going to make a decision to fund or invest into a development project which would be so bold to suggest sales prices will go down, and construction costs will continue to rise. But those exact circumstances can and do happen – most often just prior to the peak of a cycle, when peak development feasibilities are being created! That pessimistic approach is just as realistic assumption as the better looking pink and peach(y) feasibilities above.

The moral of escalation (and similarly deflation) is this. Use it to look at your upside versus your downside – sensitivity – but be weary of only showing sales prices that escalate in excess of costs to make decisions or to set inflated investor expectations. In master-planned projects, due to their longer time horizons as compared to a one-off project, the impact of escalation can easily trump all other assumptions. And at the end of the day, it’s just a big fat guess. Sure property prices always eventually rise you say, and in many growth cities of the world you might be eventually proven true, but in your ten year project will that happen in year ten or year twenty?

I prefer to use the todays-dollar feasibility, without escalation to make decisions. It’s one less assumption that is required. It also makes you appreciate the risks you need to control more – like construction costs, good old value-engineering and market appropriate design.

Reforecasting

When you sign off on the feasibility for a one-off project and start construction the feasibility typically turns into the budget. You monitor the budget as you move forward and at the end of the project review where it all ends up. Unless your one-off project has come off the rails or morphed into a master-planned project with a number of stages to be completed over multiple years, there is no need to re-forecast the feasibility.

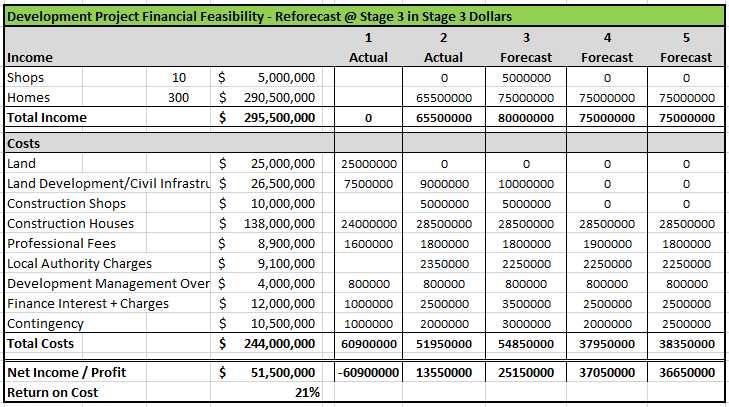

A master-planned project requires constant re-forecasting however. Rarely do you get funding or investment permission for every dollar the project will need over the master-planned projects lifetime. And from a risk management point of view neither should you. Even if you did, you need checks and balances. Re-forecasting the feasibility is the best way. At a minimum, you need to comprehensively re-forecast at each stage, to show the actuals of what has been achieved and the projections for the stages to come.

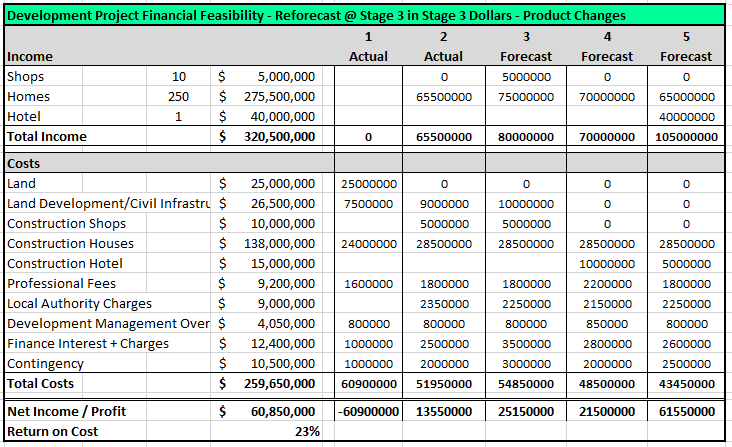

Here we put ourselves four years down the track, at the completion of stage two. We re-forecast in unescalated dollars: that is the actual dollars that were received and spent and the forecast of what is left to deliver, in today’s dollars.

It looks like we are doing a little worse than the original overall unescalated prediction (orange above). Not an uncommon site in property development! But that can reverse later down the track with a spike in the real estate market selling prices – it’s just that we are not predicting that here.

The project fundamentals haven’t really changed. We are assuming the same number of homes and shops in the same area of land. But, another big difference between a one-off project and a master-planned project is master-planned projects can evolve dramatically.

A decade is a long time for your prediction to stay the course. In all but the most fringe suburban plain vanilla – no room ever for negotiation or replanning – zoning environments, you should realize that you might have to change your product mix. And sometimes quite substantially. So four years down the track in our little scenario we find the development is still making a profit and it’s only down a few million from our unescalated original assumption. But the general area has seen an influx of businesses and office space being built. The shops we intend to sell next year look in good financial shape but a new opportunity has emerged: a mid-range hotel for business travelers. The plans have been drawn up, the numbers crunched and fed into this feasibility.

By using some of the land previously dedicated to homes to build a hotel, we can improve the overall profit by $9 million. This is a simple example, the reality can often be stranger than the fiction you predicted years earlier.

Depending on your company structure there might be a tendency to ignore the past and simply re-forecast the future. I like keeping them in the same overall master feasibility. Analyzing where you have been will lend more accuracy to your projections moving forward, especially as risks become better known.

Re-forecasting is another way of saying, get your feasibility up to date for the highest and best (aka most profitable) use of your land. The more you reforecast the better. In a good market, and you are surpassing your profit target, it might seem less urgent. But don’t rest of your laurels – reforecast to take advantage of new opportunities. Yes draw a line and keep the delivery engine running hot but don’t forget to test even better alternatives that may surface. In a poor market, you might have no option to but to spend all day testing the viability of alternative schemes, re-forecasting to save whatever profit was first predicted.

Live Feasibility

I am a strong believer in live feasibilities. This is when significant changes, new risks or risks solved are integrated into the feasibility as soon as you know about them. As soon as an assumption is clarified then you update the feaso. A cost increase – update the feaso. You can push the sales prices higher – update the feaso. Council are going to sting you for infrastructure not previously allowed – update the feaso.

This is a risk control mechanism. Even if you do this outside your normal budgeting processes. But updating the feasibility is your best way of seeing where your budget currently lies, and dealing with a potential short-fall early.

A master-planned projects overall feasibility might be massive and something you are reluctant to have open to change on your desktop every day. But someone in your team must be doing this, so you know the true financial picture of your project. Probably you! If you can’t get your head around that, then make a conscious time to update the feasibility – once a week, a month, god forbid once a quarter. Don’t leave it until you are formally required for investors, funders or the board – surprises don’t go down that well.

Now, you might not actually change anything when you update the feasibility. Because no new information warrants a change or no assumption is clearer clarified. But the key is you have gone over it and checked what you did previously assume still holds. It’s a good discipline to be regularly updating the risks and clarifying their potential financial impact and testing against the summary feasibility. Even if you only formally integrate it when there is more certainty or a significant change in the $$$.

Multiple Projects, Multiple Options, Multiple Feasibilities

A one-off project has one financial feasibility and so should a master-planned development. But the reality is a master-planned project is a collection of subprojects that will typically traverse multiple financial years and potentially multiple investors and funders. In our feasibility, maybe each stage is not a couple of years, but indeed a separate subproject determined by its location in the masterplan.

Different product types often need different types of feasibilities. If for nothing else to determine their own relative profitability amongst alternative options. For example, in our project ‘shops’ might be a small retail mall on the main road at the entrance to the development. At some point in time, it should be broken out and examined on its own. Is it 10 shops of 100m2 or 15 at 75m2? Are we selling shop condo’s to business owner-operators for a fixed rate, say $500,000 each. Or are we selling to investors who will in turn lease the space at 40,000 NNN per annum? And what yield do those investors demand? What about a few retail outlets and the rest as serviced office space? Do we really need the shops, should it be an apartment building instead? Having separate sub-project feasibilities makes it easier to handle this analysis.

Consider a billion-dollar project with a master summary feasibility where, within, each of 11 stages (based on civil infrastructure sequencing) each had its own feasibility. That was further broken down into the 36 super-lots. Big-ticket cost item issues that affected the overall development were updated in the stage feasibility, automatically updating the summary feasibility. Analysis of different product type options was done at a super-lot level – with each feasibility standing on its own. And as soon as a new product type made more profitable sense, that super-lot feasibility replaced the old one in the master.

In a flat market that involved looking at different feasibility options on different super-lots all day long trying to itch out the best profit. A new architect might have some creative ideas – so we do a feasibility. A competitor might have launched a new type of layout down the road – so we model it for our site and do a feasibility. Something a bit different comes across LinkedIn – lets test that here and do a feasibility. One day artificial intelligence might be able to automatically generate all the potential feasibilities on a site (I go into detail on that here), but until the future arrives….we do a feasibility!

So within your master feaso you need to be able to separate out the sub-projects. But they still need to link back. Always be conscious of testing a change in one sub-project’s effect on the master feasibility. Land creep is one such reason.

Creep

Land creep occurs when in order to improve one particular stage’s feasibility (usually the current stage you are ready to obtain budget approval for) land is stolen from the future stage in order to build more houses/shops/offices/stuff. The current stage’s feasibility now looks great, but what damage have you done to subsequent stages. Only by integrating it into the master (or having both stage feasibilities running side by side) can you be sure of the overall Profit and Return on Cost implication.

Density creep is another reason. This is where one stage steals gross floor area, number of units, height or whatever cap from another stage. You may have a zoning induced ceiling for the entire development. And stealing some now for short-term gain may decrease your overall long term gain.

For example, let’s say your master-planned project has ten apartment towers planned. Three have sea views. The rest won’t and everything else is basically the same. Your zoning allows you a maximum of 250,000m2 of developed floor area across the total project. [Just multiply it by ten if you are American and prefer square feet] You are leaving the sea view towers until the very last stage and are allowed to go up 50 stories and 25,000m2 each (total 75,000m2). The stage you are currently looking at includes the fifth and sixth towers, both without views. Originally you had them at 30 stories each, but you are allowed by planning officials to go up to 50 levels. You have already developed 145,000m2 and originally these two towers, in the worse location were going to be 15,000m2 each (total 30,000m2).

But the profit on this stage is not looking too smart. To improve the profit you steal 20,000m2 from the last stage and add it to this stage. Towers six and seven are now 50 stories high and 25,000m2 floor area. The profit on this stage looks great: $3,000 per m2. But the last three towers, the ones that will command the highest prices with no additional incremental cost, are now reduced to a total floor area of 55,000m2 at a higher relative profit of $5,000 per m2. When you look at the overall feasibility, you have essentially sacrificed 20,000m2 at $2,000 per m2 of profit. What’s $40mil between friends? Best to always look at the impact across the master feasibility.

Infrastructure creep is similar to density creep. Your master plan site might have restrictions or caps on the amount of sewage/traffic/power/stormwater. The allocation of this creep between stages needs to be carefully considered. Don’t use it all up in one place and leave the last stage hanging – or whatever other implication it could have.

And there probably are a dozen other creeps which you can find on your own project (Political opportunity creep, annoying neighbors creep, public amenity creep…..).

That’s enough about financial feasibilities for the time being.

Since we have introduced the concept of stages, that important difference between master-planned projects and the standard one-off development will be our next topic of discussion.

Cheers

Andrew Crosby

The DC: Master-planned Projects – All published editions.

#1 Roads

#2 Net Developable Area

#3 Feasibilities

#4 Stages

#5 Team Collaboration

#6 Architectural Design

#7 Scale Thinking

#8 Selling the Dream Location

P.S.

Now in this blurred world of social media versus professional media, my opinion versus my employer(s), salary versus side-hustle, middle of the business day versus 11pm on a Sunday evening, it can all get a bit confusing. So, here is my value proposition, and both complement and benefit each other.

- If you have a development site that you would like to sell some or all of, to develop yourselves, or to build houses then Universal Homes www.universal.co.nz might be able to help. We focus on delivering value-for-money homes in the ‘relatively affordable’ range, like the 1300 home westhills.co.nz or the 600 plus homes we have built at Hobsonville Point, or the thousands of others around Auckland over the last 60 years. Message me on LinkedIn at any time

linkedin.com/in/ajcrosby . - If you want to learn more about real estate / property development and a continuous improvement approach, with books and courses in development management to maximize profit and decrease risk then visit www.developmentprofit.com