The Developer Chronicles: Master-planned Projects

In this series, I describe master-planned projects. The discussion focuses on the difference between a one-off project and a multi-stage, multi-year planned development. I explore the factors that great development teams grapple with every day. I hope you find it of value.

AND you can also contribute to this opensource education by commenting with your own experiences, strategies, tactics and ideas here on LinkedIn. That’s where we can really embrace group network effects for continuous improvement in development management.

The DC: Master-planned Projects #4 Stages

A master-planned project, at least in my definition, is so large, complex or takes so long that it needs to be divided up into manageable chunks. Very few master-planned projects start everything at the same time but even if they do, they are likely to have their own characteristics that need to be split out. I call this ‘stages’. Others might call it phases, precincts, sectors or any other term to represent one portion of the development pie.

Stage Types

Stages can be interpreted in a number of ways, I don’t believe there is any formal categorization out there so here is mine:

- Type One. A discrete geographical portion of the total site. Let’s say a 100ha site is divided into ten, 10ha parcels. Each parcel represents one stage. So we have stages one thru ten.

- Type Two. The total development is broken down according to the chronological order of each stage proceeding. Each stage corresponds to the timing of development. Much like if each of our stages in the feasibility cashflow (described here) followed after one another. So Stage One is first, then Stage Two then stage three and so on. Each stage has its own period of development. For example, Stage One could be one year, Stage Two, three years and Stage Three, two and a half years.

- Type Three. The total development is broken down to the chronological order measured in calendar (or financial) years. So if the project starts on 1/1/20 then Stage One is 1/1/20 to 31/12/20, Stage Two is 1/1/21 to 31/12/21 and so on.

- Type Four. Product type. Stage One might be a mixed-use town center. Stage Two might be all the houses. Stage Four might be apartments.

- Type Five. Work type. Stage One might be demolition and bulk excavation works across the entire site. Stage Two might be public infrastructure offsite. Stage Three might civil infrastructure onsite. Stage Four might be above groundworks.

- Type Six. Consent type. Stage One might be subdivision consent. Stage Two a further subdivision consent. Stage Three might be an approval for infrastructure. And Stage Four a permit for building consent.

- Or, more than likely a combination of the above.

Thus, the concept of staging involves geography or timing, or both. Within stages, you might have sub-stages or super-lots or some other way of chunking that stage. And you might choose to combine stages to create mega-stages or mega-lots. And then within that you have individual site parcels.

Stage Naming

The art of naming stages, substages, super-lots and individual plots can get complicated real quick. It can end up perplexing in various ways, for example:

- Team understanding in general. We will talk about this more in a future edition but team collaboration on stage definitions is all-important. For example, a civil engineer is going to easily relate to the staging definitions given in Type Five and Type Two: a combined chronological staging of site works. So they name their plans accordingly. The architect is more attuned to what is happening above ground and takes a Type Four (Product Type approach) and names the stages as precincts, further subdivided as super-lots. The accountant only cares about staging as far as Type Three is concerned. Everyone has their own interpretation. Labeling plans and references within reports can get out of control as project team members understand stages in their own terms. I have seen it first-hand plenty of times, you can be sitting in a meeting and consultant X is referring to a particular stage, with consultant Y agreeing to everything, except X is talking about a completely different piece of land, scheduled at a completely different time than what Y is thinking about. Everyone on the team needs to be on the same -clearly understood- page as the project proceeds, and diligent in their updating of documentation. If you are in control of the project don’t assume this will be the case.

- Stages change. If you start off with a beautiful architectural master-site-plan that has every stage clearly delineated and all the definitions are time-specific synchronized in a glorified spreadsheet, I can guarantee you one thing: it will get messed up! If you were taking a sequential Type Two approach to stage names then Stage One is first off the rank. Let’s say Stage One is to do all site preparation and construction for 100 homes in one corner of your site. Stage Two is similarly 100 homes in another corner and Stage Three is a retail center located in between the two. But 3 months into planning, you decide to build Stage Three first. The conundrum is do you get the team to understand that chronologically Stage Three is occurring before Stage One? Or do you rename all your stages? Or do you add-in another definition like ‘Phase 1’ to represent timing only and ‘Stage’ represents geography or product?… See what I mean.

- Team understanding of priorities. People will naturally think Stage One starts first. So if a consultant is late to the project team party and sees a big plan on the table with Stage One emblazoned in one part, she might assume that is the highest priority. However, everyone else knows Stage Three is the priority! It’s just a matter of making sure everyone is acutely aware.

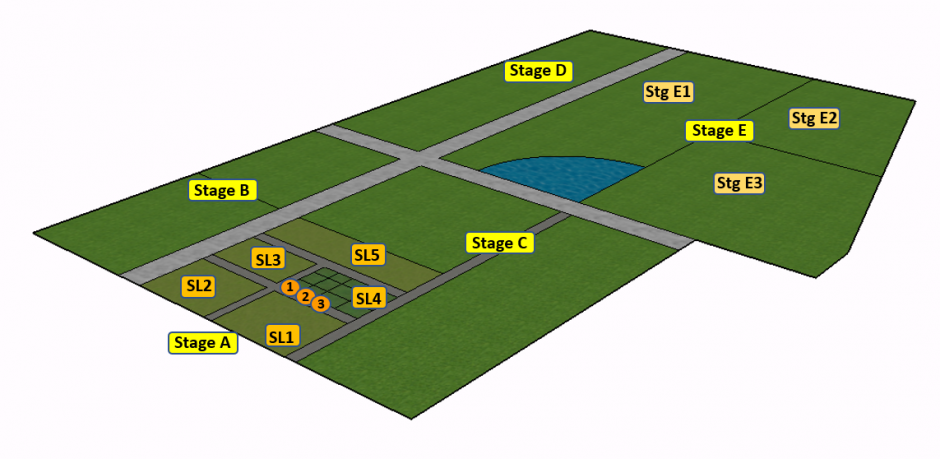

- Substages naming can conflict with master stages naming and vice versa. Take this example, you to start with Stages 1, 2,3,4 & 5. And Stage 1, includes super-lots 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 &10. Stage 2 has Super-lots 1,2,3 & 4. In a meeting if someone is just referring to super-lot 4 are they referring to the one in Stage 1 or Stage 2? There is a way around that, you simply have a numbering convention that starts at one and doesn’t repeat. Just be sure everyone knows you are talking about Stage 4 or Super-lot Four. You could have separate identifiers for stages and superlots: Stage A, contains Super-lots 1,2,3& 4. Stage B includes Superlots 5,6,7&8 for example.

- Within super-lots you might have building numbers, unit numbers and/or plot numbers. Stage A, Superlot 4, Building 3, Apartment 16. Boy that is getting confusing! If you try and use sequential numbering for plots (the individual sellable lots in a residential super-lot ) then think about the later stages: Stage Q, Super-lot 34, Lot 1256. And what if stage L is going to include 80 lots instead of 79 – do you renumber the whole sequence?

- Now, why don’t we just muddle the stormwater pond further: Super-lots might not neatly fit within master stages. So during your development Super-lot 13 which was part of Stage C, is now half in Stage D and half in Stage C. Do you break Super-lot 13 into 13a and 13b? Or what about the situation 6 months into the project when you discover a more efficient super-lot layout and combine super-lots 13 and 14? What do you call that now ‘1314’?

- And to cap it off, the arbitrary convention that created the name ‘Stage A, Superlot 4, Lot 56’ now succumbs to a formal legal definition once Title is issued You may of may not be able to control what name becomes. You certainly won’t if you don’t coordinate with your lawyer and your land surveyor (or whoever is preparing Title documents). For example ‘Stage A, Superlot 4, Lot 56’, becomes Lot 14, DP 13598.

What’s the moral of this discussion (that you will have rapidly lost interest in) about convoluting numbers turning something that should be simple in an algebraic mess?

Well, you need to control your numbering conventions on a master-planned project and keep close tabs on them. Someone should be in control of numbering. You will be amazed at how confused the wider project team will get if you don’t. [This is also a plea for someone out there on the interweb to let me know the best way to number master-planned projects…]

Here is our master plan from the last edition with the naming upgraded to reflect some of the issues.

Staging

You have developed a foolproof robust numbering/definition system for all the stages/super-lots/plots on your master-planned development. But, where do you actually start bringing in the bulldozers?

On a 200ha, 3,000 home and 50,000m2 of mixed-use (apartments + retail + office), do you just go and build the whole thing? In most cases, of course not. That’s why we have stages. But why do we choose a particular stage to be the first, the last or seemingly somewhere random in the middle?

Here is what the development team needs to consider when deciding, where to start. And be warned, different members of the team will only see their part as the priority. So depending on the outcome desired (which in the ideal world should really always be distilled to maximize total project profitability) any one of these factors may take precedence over the other. Sometimes it will be a no brainer, other times a hard decision will be required.

- Market velocity. What can I sell the fastest? You might need the cash or to give investors a little upfront faith in the market. If the housing market is flat but the office market is booming, then you might have to compromise your original plans and start with what will bring in some contracts. Of course, everything has a…

- Market pricing. Price. Yes, everything has a price. Sales velocity is typically related to pricing. Without reducing quality or speed, the lower the price the more sales. Not always. But where you and your competition are all doing the same thing – and your development product is essentially a commodity – price matters. And when real estate markets retreat, lower price and affordable often trumps high price and luxury. So you decide the first place to start is where you can deliver the lowest price-point properties. Or, in an upwardly accelerating market, it could be time to capitalize on all the loose money and sell more expensive homes – the waterfront stage first perhaps.

- Brand establishment. One big difference between master-planned projects and one-off projects is ‘estatewide’ branding. The first stage of your project will set the scene for what lies beyond. It’s your project curb appeal. Do it nicely, and you can build up sales momentum to continue to the other stages. So the decision might be to start with a stage that includes high specifications, stamping the seal of quality on the project from the outset. The brand is more than just your product though. It is also what else your master-planned project can provide. And that includes…

- Amenity. A common formula is to build parks, lakes, waterfront esplanades, ski-lanes, golf courses, wetland sanctuaries, playgrounds, public plazas or whatever ‘drawcard’ your project has upfront (like these). That helps your brand, by providing buyers or tenants amenity to use from day one. So your first stage may simply be all of the communal amenity with immediately ensuing stages those that are close to those features. Conversely, you may first need product to be developed to establish market demand. Think of the shopping center in the middle of a new housing suburb. You need the people living there, to build a customer base before you can attract retail tenants. Retail follows roof-tops is the old adage (but not always applicable).

- Profile. If your first stage is to set the scene, for a decade or so of fantastic developing ahead, then the place where your project site gets the most profile could be the best place to start. Maybe that’s beside the main road. Top of a hill. Viewable from the freeway. Next to an existing shopping center.

- Public Relations. Perhaps the profile you are harnessing is not physical but something more ethereal. Do you need to make a statement and build the publically aware affordable housing scheme first? Or the more ‘green and sustainable’ parts of the project? Alternatively, could this be a development where you want to keep a low profile, say a heavy industry, industrial park? So you begin with whatever is furthest from sight and mind.

- Demand. In a purely private profit-based development, demand is linked to both market velocity and market price. However, if you are developing in conjunction with a government housing provider then you might need to satisfy demand from a homelessness waiting list. That stage of the development might be first off the rank. Or post a natural disaster, the commercial section of your site might now be the place for businesses to relocate from their damaged offices. I recall Christchurch where the entire CBD had to up and leave for the suburbs. A similar situation happened in the wake of 9/11 in New York.

- Livability. Few people like living or working next to a construction site. No one really wants their kids strolling to the local primary school while 18 wheelers motor down your suburban street full of rubble leaving a dust trail in their wake. Your high profile tenant taking 20,000m2 of your suburban office park is going to lose their patience if you are detonating rock in the hillside next door 9 to 5. The staging may have to take explicit account of post-occupancy livability (or workability).

- Access. It might be a simple as getting stuff in and out. Perhaps there is only one road to your master-planned project and Stage A is where that road first hits your boundary. Or perhaps there are multiple access points to choose from, so you choose the one that allows the most efficient construction. Sometimes – especially with urban brownfields- you must keep the end in mind and start in the deep reaches at the back of your site, so you don’t box yourself in

- Civil works constructability. There could be other constraints on your site which dictate where you build first. It might be necessary to excavate a hill first to fill in a valley elsewhere. Otherwise, you are stuck with a pile of dirt you can’t get rid of. Or, the soil on part of your site might be the highly expansive peat (think dirt in an ancient swamp or bog) and you need to compress and let it dry for months or years to ‘settle down’ to a natural level.

- Above ground constructability. Maybe you want to get rid of difficult construction on a hillside, next to a river or along the coast first. Or perhaps, at this initial point in time, only building single level family homes sits within your development sphere of expertise. The apartments you have planned will need to wait until later stages when you expect you will be better equipped.

- Civil construction cost. If your site has no redeeming features, no locational value differential, one product type and not a lot else – imagine a sea of standardized homes, with the same beige roof, in the same grid-like (or so 60’s cul-de-sac type pattern) – then it might be as simple as focussing on what purely is the most efficient and economical way to build out the site.

- Seasonality. In wet climates, you may be restricted to bulk earthworks to the summer months. That could impact your staging to make the most of your earthworks season. Similarly, for snow, you might not be able to do any construction – how do you maximize the summer? Or in extremely hot climates, how to do you maximize the cooler winter construction season? And then there are those pesky holidays like Christmas and Chinese New Year that for human resource reasons determine a different staging agenda.

- Infrastructure. Let’s say you have to build a main arterial road through your site, but you haven’t quite agreed with the authorities its exact location. Without a resolution. you might be precluded from developing areas adjacent to that road. It might prevent you from developing areas a long way away from that road as well, due to having to allow for levels and the flow-on effects of one roads location on other roads in your intended site network. Roads (as we have discussed before here) can have a big impact on staging. Or what if your project is limited in allowable retail square footage until the local authority has upgraded the intersection on the main road out the front? Or the wastewater authority tells you they only have the capacity for homes on the half of your site closest to their existing network? And that just happens to be the half you originally wanted to develop last – and the rest has to wait until the neighboring developer builds a new pipe.

- Neighbors. Talking about boundary buddies. Neighbors can influence which stage you commence for a variety of reasons. Look at those NIMBY’s where you simply can’t get permission from them for whatever reason (to buy their piece of land, push height to boundary rules, require an easement for access or services, want to build a shared retaining wall, must get their permission to shore up their building foundations etc). That may compel you to commence a different stage earlier, as you wait them out, or simply buy time to think through a new strategy. Or perhaps your neighbors at one end of your site are in the swankiest zipcode in town. So beginning the development closest to them helps your project from a prestige and profile point of view. On the other hand, maybe your site straddles a complex which at best, is politely described as Hotel California. This neighbor might give you reasonable cause to start your development as far away as possible.

- Existing buildings & land tenure. You may have to stage works around parts of your site because there are tenants still in business, leases still left to run or rental agreements with home occupiers. You may want to continue some leases or lease out existing space to create a revenue source whilst you undertake your design and planning. Sometimes existing buildings are a cost-effective construction headquarters or make for an ideal shell for a marketing showroom. Typically, the ideal structure is to move all tenants to periodic terms and a ‘demolition clause’ that allows you to remove them with say up to 6 months notice.

- Flexibility. Maybe there are just so many issues to deal with, that retaining maximum flexibility for future planning, is the top priority. So you focus on the stages that have no alternative option first.

- Clarity. Similarly, the first stage you start with has the most clarity. The market is certain, the risks exposed, the issues are sorted. Subsequent stages are based on the level of clarity you reach, by the time you need to start the next stage.

- Risk and certainty. In the same vein, what stage represents the lowest risk? – let’s start with that. Which stage do have close to zero visibility on what we are going to do -let’s leave that to last.

- Timing. Speed could be your prime aim. What staging is going to get this project finished in the shortest amount of time? It might be a self-imposed restriction. Or imposed by your investors, funders or government regulations (like when zoning could expire or you are subject to government-imposed investment controls). Or is patience your forte? You want to stage the project so you do the absolute minimum to cover costs, whilst you go for the rezoning profit jugular with a planning application that might take half your children’s school years to get approved. Or you are simply content (and wealthy enough) to wait it out until the market improves, and your land value with it.

- Profit. All things considered, what makes us the most profit? – Isn’t this the only reason to choose a place to start? It can get hazy though. Does your profit include assumptions about value escalation created by early stages that will hopefully increase the value in later stages? Is it this financial year’s profit you want to maximize? Or maybe you are a listed company, you can only see as far as the next quarter’s profit (not always the best focus for long term real estate developments)? Is it the total overall project profit to be maximized? Are you measuring that in absolute dollars – the highest number of suitcases filled with greenbacks this project will deliver? Or are you measuring it in cash on cash return? Or the internal rate of return? That could lead your staging strategy to focus on maximizing net revenues versus expenses over time.

- Cashflow. Finally, (at least for this list) how does your staging take into account project cashflow? You might have plans for lakes, an aerodrome and an equestrian park to rival badminton, but your bankers simply aren’t going to pony up the money for all this extravagance (in their eyes, in yours it’s all value-add!) until you get some revenue in. Your staging plan may then have to focus on those stages that create higher revenues and lower costs early on and save stages with larger costs (like public infrastructure upgrades) to later in the project. Or do you have the financial clout to take advantage of lower costs for expensive items now rather than face cost escalation in the future?

If you have had the pleasure of working on a master-planned project of any significant size then you know, it’s likely many of the above factors are going to play a role. Some appear obvious (in the absence of complications who doesn’t want speed and profit?). Most overlap in multiple ways. And that list above is not even the half of it.

This is not a one-off decision though. It’s not just where you start, it’s everywhere you continue. You might need to consider all the same factors multiple times throughout the development timeline. Or some factors may need to be set in stone, because of long lead times, or commitments. Then, regardless of what makes the most sense (perhaps from a profitability perspective), you are forced to stay to course.

A master-planned project requires you to make a lot of decisions regarding staging and the timing of those stages. That makes it significantly different from a one-off project And it takes a whole lot more teamwork and coordination – which leads us to the topic for next time.

Cheers

Andrew Crosby

The DC: Master-planned Projects – All published editions.

#1 Roads

#2 Net Developable Area

#3 Feasibilities

#4 Stages

#5 Team Collaboration

#6 Architectural Design

#7 Scale Thinking

#8 Selling the Dream Location P

P.S.

Now in this blurred world of social media versus professional media, my opinion versus my employer(s), salary versus side-hustle, middle of the business day versus 11pm on a Sunday evening, it can all get a bit confusing. So, here is my value proposition, and both complement and benefit each other.

- If you have a development site that you would like to sell some or all of, to develop yourselves, or to build houses then Universal Homes www.universal.co.nz might be able to help. We focus on delivering value-for-money homes in the ‘relatively affordable’ range, like the 1300 home westhills.co.nz or the 600 plus homes we have built at Hobsonville Point, or the thousands of others around Auckland over the last 60 years. Message me on LinkedIn at any time

linkedin.com/in/ajcrosby . - If you want to learn more about real estate / property development and a continuous improvement approach, with books and courses in development management to maximize profit and decrease risk then visit www.developmentprofit.com