The Developer Chronicles: Master-planned Projects

In this series, I describe master-planned projects. The discussion focuses on the difference between a one-off project and a multi-stage, multi-year planned development. I explore the factors that great development teams grapple with every day. I hope you find it of value.

AND you can also contribute to this opensource education by commenting with your own experiences, strategies, tactics and ideas here on LinkedIn. That’s where we can really embrace group network effects for continuous improvement in development management.

The DC: Master-planned Projects #6 Architectural Design

Like any one-off project, for a master-planned project, you have to come up with architectural design. A site plan, building floor plans and some elevations. One key difference with a master-planned project is there are multiple layers of design.

Urban Design

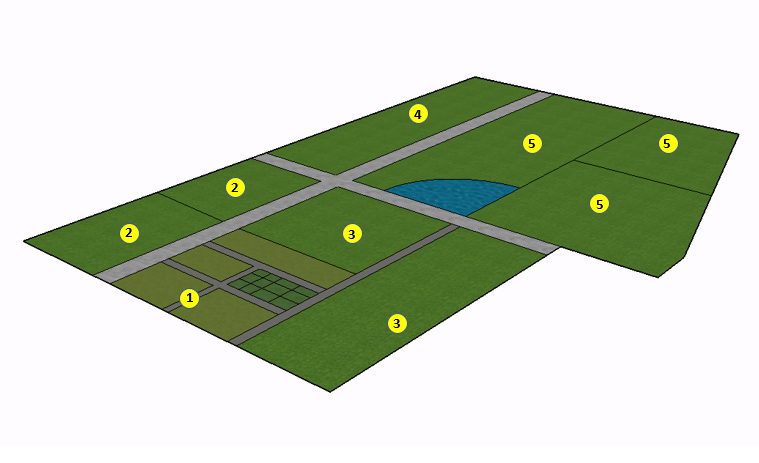

First, and most different from a one-off project, you have the overarching layer of urban design. This is (or some say informs) the general layout of your site, all its key amenity, roads (we looked at roads in detail here), geographical constraints and the stages and/or super-lots within.

All developments have some aspect of urban design. Building design and urban design often morph into a grey zone, where both building architects and urban designers claim it’s their space. Where on the site do you place a condo tower? How does it interact with the public-facing street? What connectivity to the neighboring streets does it enable? And so on. But with a master-planned project, by virtue of nothing else but its size, duration and having to build transport corridors, we are designing a completely new urban environment.

There is a tonne of definitions out there. The Urban Design Group in the UK have summarized plenty here. I quite like the following two as they cover both space and time in the context of a development project.

“Urban design involves the [spatial] design of buildings, groups of buildings, spaces and landscapes, and the establishment of frameworks and processes that facilitate successful development.” – UDGUK

“The process of molding the form of the city through time” – Peter Webber

At the end of the day, regardless of how theoretical we muse, urban design produces a number of practical outputs. The big one is the master-plan or master-site-plan. This is the picture of where all the roads, lakes, parks, shops, offices, homes, warehouses or factories are located. To get there might have been quite a process, and like Mr Webber above describes, it can change over time. Something a bit more detailed than the high level one we discussed here.

The more diverse your master-planned project, they more complications urban design must embrace. Flat is easy. Hilly gets difficult. 1,000 standalone replica 200m2 houses on 400m2 lots on the same road grid, surrounded by clones where sales agents can’t even touch the sides of demand is easy. 700 houses comprising of seventy-eight different floor plans across a range of lot sizes with a town center, a small industrial park, and all next to an existing airport on a peninsula in a soft housing market is not so easy.

One way urban strategists in the project team approach creating the master-site-plan is to break each ‘complication’ into an overlay. The objective of each overlay is to create the best response to that complication. Then you lay them on top of each other. In the perfect world they all line up and then you can start drawing your response – the master-site-plan. Of course, they rarely do and compromises need to be made. That’s where the priority comes into play.

What’s the biggest priority? Profitability – certainly if you are a private or corporate developer. So one of your overlays – the most important obviously – is financial. Obvious to developers and bankers at least. Unfortunately, urban designers are typically architects and profitability might not be always so obvious to them. Master-plans can be heavily influenced, if not dictated by infrastructure, geo-technics and traffic – again profitability might not be so obvious to the engineers either. So the urban design process needs a financial overlay. That means your financial feasibility (as we talked about a few editions ago) is an integral part of the urban design process. As your designer starts drawing site responses to complications, the development manager/ feasibility manager needs to fire the feaso up. You can’t simply leave the urban design to the designers!

You have to start somewhere though, and there is a short-cut that gives the urban designer somewhat of guiding spatial light as to what could constitute maximum profit: maximum density. Thus zoning is an important overlay. In many rising real estate markets, especially over the long term maximizing the allowable Net Developable Area, and then the Gross Floor Area on top of that will be a good proxy for maximizing profitability. If your site already has zoning determined, then much of your urban design framework may be set in stone. Retail here, commercial there, residential elsewhere. If you are starting with the purest of greenfield sites and have the flexibility (and deep pockets) to create your own zoning then each other overlay becomes that much more important.

Let’s look at some other overlays:

- Transport links. Rail stations, freeway access, arterial roads, bus-stops, ferries, and other big-ticket transport connections. This overlay will certainly influence where you place retail and commercial activities. Housing not too close, but not too far (unless lifestyle or rural blocks are your taste). Higher density at the nodes, lower away.

- Topography and physical geography. Hills and valleys. Flat, rolling or sheer cliffs. Streams, rivers, lakes, the coast, and native forests. Some natural features present opportunities and others constraints.

- Sunlight. North-facing or south-facing slopes. Shadow lines from hills, trees or any buildings across the boundary.

- Amenities. Proximity to town centers, places of recreation, schools, medical facilities, beaches, centers of employment, tourism and industry.

- Infrastructure. Where the ‘big’ pipes have to go. What areas can be serviced, which can’t? Powerlines in the way?

- Views, outlook, privacy, quiet, areas where you can enhance profitability, by charging higher rent or sales prices.

- Geo-technical. Soil type, overland flow paths, flood-prone, flood management areas. Yes, you can build on anything, just depends on the expense to do it.

Like almost everything in real estate development, nothing is crystal clear and many overlays influence each other. Where the relationships are not clear, break them down into the simplest layer possible. For example, break topography and physical geography down to buildable areas and non-buildable areas. Or school zones might be deserving of its own overlay.

And you will note that when you look to stage a development, many of the same influences crop up. The urban design will evolve over time. As each stage proceeds, you might be reevaluating urban design for the next stage. This is where Peter Webber’s quote above comes into play.

It’s an iterative process of working through each overlay and its relative priority to maximize opportunities and minimize negative effects of constraints. This alongside constantly analyzing the income potential and the cost ramifications to help prioritize.

With the overlays in place the urban designer can draw a first-cut of the master-site-plan. Then the team must refine, and refine and refine and refine…..fully aware that as time goes on, what you are refining now might not come to be. Refinement never sleeps in a master-planned project.

Superlot Design

Super-lot design is the next layer. A super-lot is defined as a contiguous piece of land within public roads. You can sell it on its own, or you can subdivide further into individual plots for houses, a block of shops, an apartment tower or a logistics facility. Regardless you need to have an idea of the types of buildings -almost always the highest and best use of that super-lot – that will occupy it.

Roads (as we discuss here) have a big part to play determining a super-lot’s external boundaries. But now we must think about the specific buildings and sellable parcels of land within. A single super-lot might be so complicated to require specific urban design all on its own. This is especially so if you are mixing uses in the same super-lot. You may need to apply an overlay approach to the design within the super-lot.

With that in mind now you can design the most efficient, most profitable super-block. And once again, get your calculator out. Crunch the super-lot’s own feasibility as the architects put forward design options.

Additional considerations for super-lot design:

- Sellable land efficiency. Are we allowing for the most efficient and sellable lot sizes and layout?

- Flexibility. Somewhat contradictory to the previous item, does your super-lot allow different types and shapes of plots and buildings that could adapt as markets change over time?

- Is the super-lot efficient and flexible in terms of infrastructure? The cheapest approach will be to provide as many individualized service connections (think driveways, wastewater, stormwater, power & utilities) at the same time as you construct the super-lot. However, this may preclude flexibility (at least at a cost) within the super-lot later on.

- Streets. Roads that surround the super-lot contain elements that cannot be adjusted very easily – and when publicly owned, moving anything might prove next to impossible. Streets can constrict the design within the super-lot, despite how much future-proofing you are trying to cultivate. Street trees, parking bays, rain-gardens, utility ‘boxes’ (like power transformers & sewage pump stations), power lines, street lighting, leased billboards, cellphone towers and bus-stops to name but a few.

Building Design

The stuff that everyone really looks at: the vertical build. What can be different between a one-off project and a master-planned project? That depends on how as a development company we are structured to deliver:

- Land subdivider. We are creating the urban framework and developing all the land, but we intend to sell all parcels/super-lots off and let others build at their discretion.

- Land to letterbox. We are developing, designing, building and selling everything.

- Bit of both.

Whichever development approach, a master-planned project requires additional thinking that a one-off project is rarely concerned with. If you intend to sell land to others, building design is all about control. Controlling the branding, the look and feel, the quality and most importantly the master-planned project’s long-term profitability. If you have rezoned the entire estate then that is one control. Albeit, that might be limited to density and bulk and location restrictions. The other often used control is to create and enforce design guidelines.

Design Guidelines

Design guidelines can be legally attached to the titles as covenants and/or stipulated as part of the sale and purchase contract and/or included in the rules enforced by an incorporated society representing owners in the master-planned estate. Tieing the guidelines to current and future owners is important – so the rules run with the land. This often means that design conditions in the sale and purchase agreement are not legally sufficient to protect the developer from a subsequent future transfer of ownership.

What’s in these design guidelines?

It’s your project so pretty much anything that doesn’t contravene the law! I recall one subdivision in Phoenix tried to ban people flying the American flag – that didn’t go down to well, with pretty much everybody except the committee who dreamt up the idea. However, in the context of a master-planned project, design guidelines are more than just resident restrictions. Rules like no parking on the lawn, don’t put washing drying over the front balcony or limiting dogs to less than 50cm long. All the impediments to daily life. Saying that though, design guidelines and resident rules do overlap. No tarpaulin (poor man’s sailcloth) over your pergola – is a rule (yes a real one put in place by a least one government housing provider) to protect neighbors from the unruly design-inconsiderate antics of those living next door.

We’ll start with the objective of having design guidelines. And if we strip it back to its core, it’s fairly simple: design guidelines are to protect the master-planned project’s developer’s profit. You can spin this a different way of course and say “design guidelines protect the home buyers investment” or are the “design guidelines enforce quality and reputation of your working environment and shopping experience” or “design guidelines to protect the integrity and desirability of the ‘Blue Vista Estates’ brand and name” – all of which might be true, at least in the beginning.

You see when you commence a development you may have very strict design guidelines. ‘Guides’ (which are actually rules) that prevent builders or mini-developers – that you onsell super-lots and parcels of land to – from designing and building any old visual debris. Design rules that are typically over and above what the local jurisdiction allows. Here are two common, albeit blunt, examples:

- “Minimum floor area of 250m2.” This rule sets a minimum size, which indirectly pretty much guarantees a higher price point.

- “Must build by 1 December.” This rule ensures development occurs as quickly as possible – both so empty sections are not left growing weeds and to stimulate demand.

Then there are design guidelines that take it further and prescribe building forms and aesthetics:

- “Allowable cladding materials include brick and timber weatherboard. Timber or commercial grade aluminum window joinery only. PVC siding and windows is prohibited.” This rule attempts to prescribe higher specification exterior materials.

- “No hip or flat rooves.” This type of rule attempts to restrict architectural styles seen not in keeping with the overall development.

- “Garage doors must not face the street.” A rule where the developer is trying to create the illusion of no cars, or at least prevent the dominance of garage doors on front elevations.

- “The upper level must not exceed 50% of the floor area of the lower level.” A guide intended to create an architectural style that forbids boxy developments.

- “Fencing is to be 50% permeable and no higher than 1.2m along the front boundary.” Intended for looks or passive ‘eyes on the street’ surveillance.

- “Front facades must contain a minimum of 50m2 of glazing and a fully landscaped front yard.” Think of the industrial park trying to push a half-decent looking streetscape.

The list of guidelines can run deep. And to help explain you might need to include example drawings and pictures. Guidelines can easily morph into a hefty design manual if you are not careful – in an attempt to fully describe the architectural response the master-planned project developer is looking for. Fairly soon though you run into design rules that are open to interpretation, and potential abuse or technicalities (from the master-planned project developers perspective). So to protect the master-planned project a formal approval process often accompanies the documentation.

The approval process might be as straightforward as ‘all plans must be signed off by the developer prior to construction’. Or it may be a bureaucratic multi-step approval board rivaling (or occasionally with permission replacing) local authority design review panels. A panel might have a representative from the developer, the city and a few architects thrown in for good measure.

Then there is the extreme version of architectural prescription. Not really design guidelines as much as ‘this is the design, now go build it’. Like a book of allowable concept designs or consented plans with no option to modify. This is where the master-planned project developer wants micro-management control over the design (and quite possibly retail selling prices), without actually building and selling the end product.

Design guidelines, especially exacting ones can work quite well when the following circumstances exist:

- The market is booming, demand outstrips supply and generally, everyone is prepared to pay for the privilege to live or operate in a design guideline adjudicated environment, and

- The urban design guidelines accurately reflect the real market for the product to be developed.

However, when the market softens it takes a very stoic developer (and investors/funders) to stick by the design guidelines, especially when they are causing (short-term) profit pain. I have seen countless subdivisions that start with all sorts of restrictions and the nicer (more profitable) homes are first of the rank to be sold and built. Then as the market deteriorates they (or the receivers) throw the design book away to make land sales. Inevitably lower ‘quality’ product gets built. And at that point, the project is on a race to the bottom. The ability to turn back to design higher-end (and more profitable) product as the market improves may now have been severely compromised.

But sometimes, in false hope, you create ‘design misguidelines’. This is when the vision and the reality don’t quite gel. Often in an area where gentrification is before it’s time, or a greenfield site that doesn’t support the underlying value proposition: amenities, schooling, socio-economic wealth, employment etc. Yes, you can sell land that enforces such quality controls at the peak of the market, but in all other times, you are effectively handicapping your potential land buyers.

So the takeaway is to produce design guidelines that are both sustainable and enhance profitability over the lifetime of the master-planned project.

Design at Scale

Is this one project of 1,000 homes or 1,000 home projects?

If you are developing and building the entire master-planned project then you have to think of design at multiple levels. The overall urban design – the big picture. The stage level. The super-lot level. And the individual plot (or lot, or section or whatever quasi-legal term you use) level – the nitty-gritty detail.

With a residential subdivision project of say 3,000 semi-detached homes, or 30 apartment blocks or 20 office towers, you have the opportunity to think at scale. Something you don’t get (as much) with a one-off project.

‘Thinking at scale’ has plenty of positives for efficiency and productivity, in design – for example:

- If we build a consistent volume of 300 houses a year, every year for next ten years, what sort of bulk supply agreements can we enter into with architects, engineers and other consultants?

- What if we just design one office tower and replicate it 20 times?

- What about 5 standard house plans, that we replicate 600 times each?

- What about the exact same configuration for each superlot?

- Can we get a global building consent so we don’t have to apply for each individual building?

And that all works where you are taking a cookie-cutter approach. But there are design drawbacks, especially in projects with a large residential component. This is what I call ‘at scale complacency’.

At scale complacency occurs when the details are glossed over, just because there is a big number. And in a master-planned project, one of the biggest offenders are architectural designers.

Consider this scenario, you hire an architectural firm to design three super-lots of 100 terrace homes each. The architectural firm charges a fee based on a per-home basis. You get the designs back and it all looks the same. The colors are similar. The plans are similar. The windows are in similar positions. The roof forms are similar. The decks are in the same place. The designers have put plenty of thought into the big picture look and feel but have they adequately addressed the detail?

Your modus operandi may have been to cut costs and boilerplate everything. Standard floor plans. Standard colors. Everything a carbon copy. That is a valid strategy if it truly reduces your costs and your master-planned project branding and ‘look and feel’ and most importantly the buyer pool that you are targeting can handle it. But often it’s not. Even if you have brought into the architect’s ‘vision’ that they have designed a cohesive design that links all the homes together in a symphonic melody, you need to check out the detail.

As development manager or design manager, you might only be interested in the stratospheric perspective of each super-lot or stage. From that high-level design view the architect may have done an exemplary job.

All the same the home buyer might not think so. And who is your real customer – the architect or the home buyer? The designer or the tenant? And what do they really care about?

I won’t keep you guessing.

They ONLY CARE about their new home, new office or new shopfront. Sure you might like to skite to your friends about being part of a brilliantly designed award-winning masterpiece courtesy of starchitect so and so. But how is that going to go down when you are sitting on your deck, toasting a chardonnay with all your mates looking out onto a big ugly confronting retaining wall? Especially whilst your 5-year-old daughter, sitting in her bedroom, without even straining, has a panoramic view of the city skyline!

The buyer cares about all the details. They are going to live or work with the details. On a site plan with 100 homes, the buyer is not going to see the finer points in the design. But once the property is built, every detail will be out in all its glory. Unless you have pre-sold or pre-leased and have a thick skin to suffer the abuse from an irate buyer or tenant and the market is so hot, replacements will line up regardless, then I suggest you pay attention.

No not just you, the architect needs to. Train them, coach them, politely remind them, throw their fee letter back at them, whatever, but get them to look at every single individual building and unit to maximize value. Have they imagined themselves on every deck on a summers evening? Do they pay attention to what one will see from the kitchen window, and every other window? Does the fence block a potential parking space? Could the trash can go in that corner? Why not put the transformer around the corner, out of sight? Can a kid play on that gradient? Will we get more sun if the window is higher? What does the room feel like with that metal detail over the window? Yep buyers have emotional attachments to what could be their biggest investment.

Yes, a big list of design considerations, applied to every single unit can be intimidating. Does your architect even have a checklist for such concerns? Don’t let them become complacent with scale. Especially if you are paying them a similar per-unit rate regardless if it’s 10 or 100 units. Even if you have a bulk discount, this level of spatial thinking needn’t take that long. But it does take the mindset to think like the eventual occupier for every space that is designed.

When you are designing your own home, you and your family are across every single detail arent you – from light sockets to window sills? So get your architects to take a similar approach when designing ten thousand!

Now, what if you don’t buy into the architect’s design consistency argument? You actually want your master-planned project to have architectural variety. You might be creating the city’s next suburb, but that doesn’t mean it has to all look the same nor should scale mean compromised individuality. You have told the architect but you are not sure if they are getting the message. You know when the architect comes back on the third attempt and terrace block 15 still looks the same as terrace block 12,13,14, 16 and 27? When apartment tower X looks surprisingly similar to office tower Y. In this situation not only are the design team suffering from ‘at-scale-complacency’ they are caught in a vicious case of tunnel vision. Well, from experience there is only one way out.

Hire multiple architects.

And on that note, look out for our next edition where we explore everything else about scale.

Cheers

Andrew Crosby

The DC: Master-planned Projects – All published editions.

#1 Roads

#2 Net Developable Area

#3 Feasibilities

#4 Stages

#5 Team Collaboration

#6 Architectural Design

#7 Scale Thinking

#8 Selling the Dream Location

P.S.

Now in this blurred world of social media versus professional media, my opinion versus my employer(s), salary versus side-hustle, middle of the business day versus 11pm on a Sunday evening, it can all get a bit confusing. So, here is my value proposition, and both complement and benefit each other.

- If you have a development site that you would like to sell some or all of, to develop yourselves, or to build houses then Universal Homes www.universal.co.nz might be able to help. We focus on delivering value-for-money homes in the ‘relatively affordable’ range, like the 1300 home westhills.co.nz or the 600 plus homes we have built at Hobsonville Point, or the thousands of others around Auckland over the last 60 years. Message me on LinkedIn at any time

linkedin.com/in/ajcrosby . - If you want to learn more about real estate / property development and a continuous improvement approach, with books and courses in development management to maximize profit and decrease risk then visit www.developmentprofit.com